The Kunágota Sword-Guard - Professor Valeri Yotov

Jun 26, 2013 10:29:33 GMT

Post by Jack Loomes on Jun 26, 2013 10:29:33 GMT

THE KUNÁGOTA SWORD-GUARD AND TWO BRONZE MATRICES FOR SWORD-HILT MANUFACTURE FROM IRAN

Download or view PDF here: Kunagota Sword.pdf (2.49 MB)

By Professor Valery YOTOV

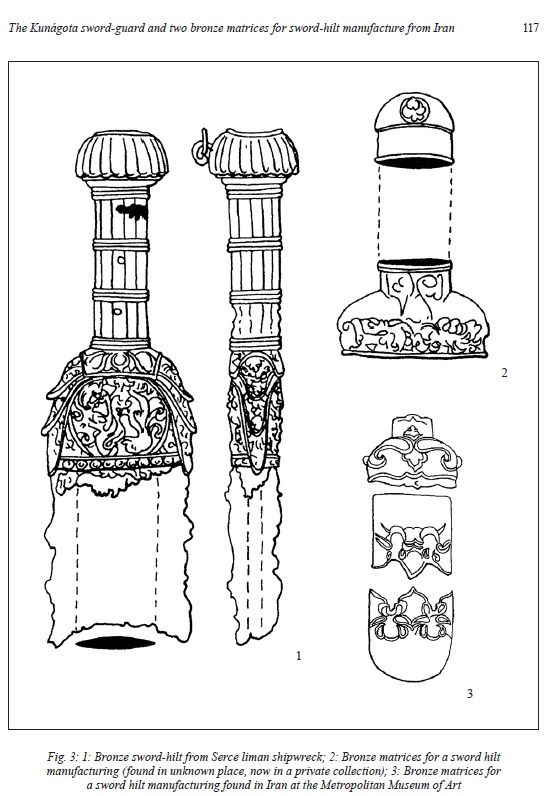

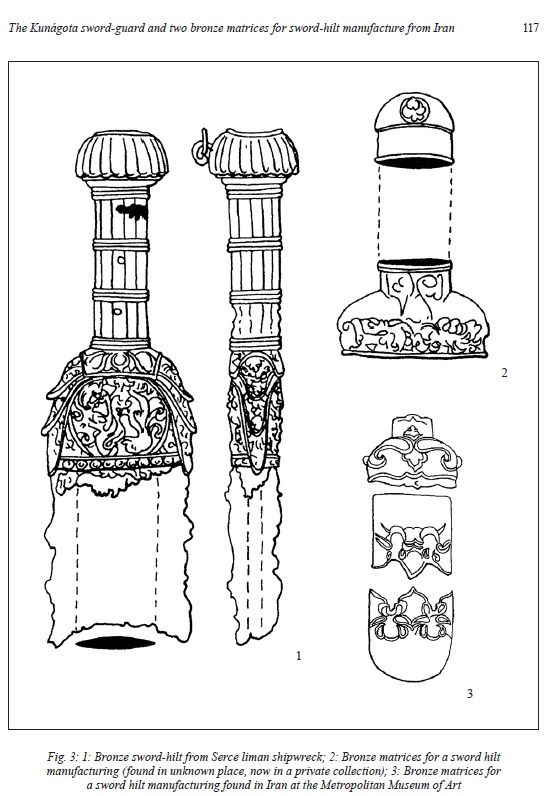

In 1926 a sword with a bronze sword-guard from Kunágota (Békés County, Southeast Hungary) was published by F. Móra (MÓRA 1926, 123–135) the remarkable researcher and director of the Szeged Museum (Fig. 1).1 In several articles published by Hungarian specialists in recent decades, this interesting artifact (its sword-guard being the main issue commented upon) was defined as not being typical for the Carpathian territory and was subsumed under a group of swords regarded as being of Byzantine origin (BAKAY 1967, 172; BÁLINT 1991, 110,Abb. 31; KISS 1997). The sword was discovered in a destroyed grave together with a couple of stirrups, two earrings and a solidus of the Byzantine Emperor Romanos I (920–944) (Fig. 2). Both the grave and the cemetery are dated, beyond any doubt, to the period between 930s and 950s (KOVÁCS 1993, 46, 51). Until now the Kunágota sword, and the swordguard especially, were not compared to artifacts similar in shape (BÁLINT 1991, 110).2 This has also been noted in the analytical work of A. Kiss (KISS 1997, 200). During a visit to the Institute of rchaeology in Budapest, and due to the kind help provided by Hungarian colleagues, I had the opportunity of getting acquainted with articles and books by the English researcher D. Nicolle on medieval arms and armour. In the chapters discussing the Byzantine Empire, together with a large number of artifacts, the presents two bronze matrices for the manufacture of sword-hilts: one of them now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fig. 3. 3) and the other from a private collection (Fig. 3. 2). Both are believed to have come from Iran. D. Nicolle wrote that both artifacts are dated to the 12th–13th to 14th centuries, but he also drew attention to the fact that “the dating of these objects is very difficult” (NICOLLE 1999, Kat. Nr. 543-a, 676; NICOLLE 2002, Kat. Nr. 29-A, 30).

The Kunágota sword-guard has several main typical features — a high sleeve, cylindrical in shape, of the upper section, arch-shaped levers and a sleeve with an ellipsoid bottom section. These characteristics are very close, indeed almost identical to, the shapes that the matrices would produce for the moulds and the manufactured artifacts. It is especially true for the matrix from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which has almost the same curves of the bottom part (the larger sleeve) and the palmette-shaped decoration on the upper part.

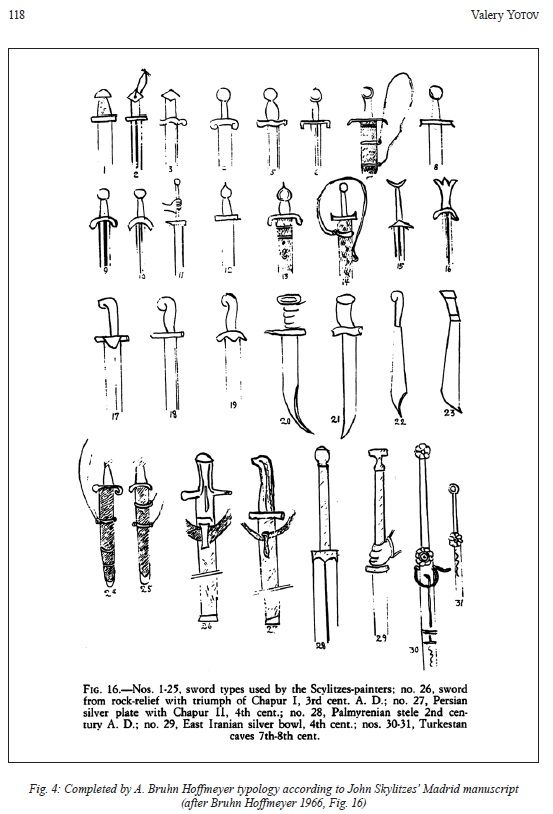

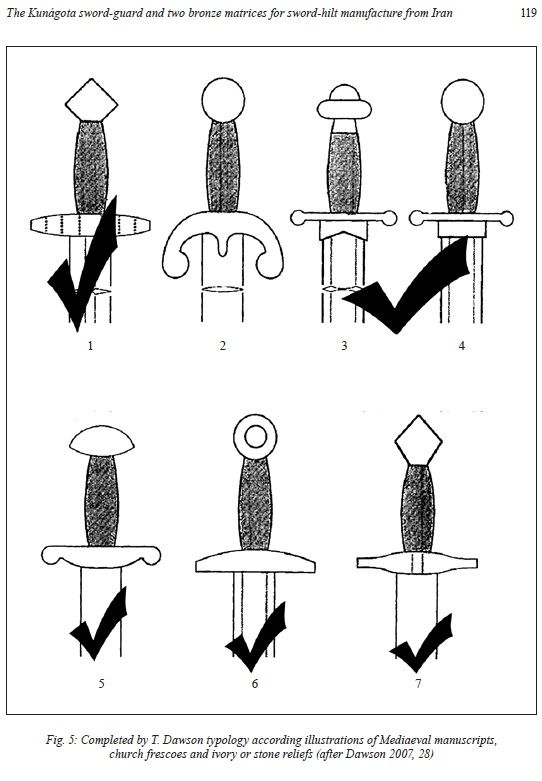

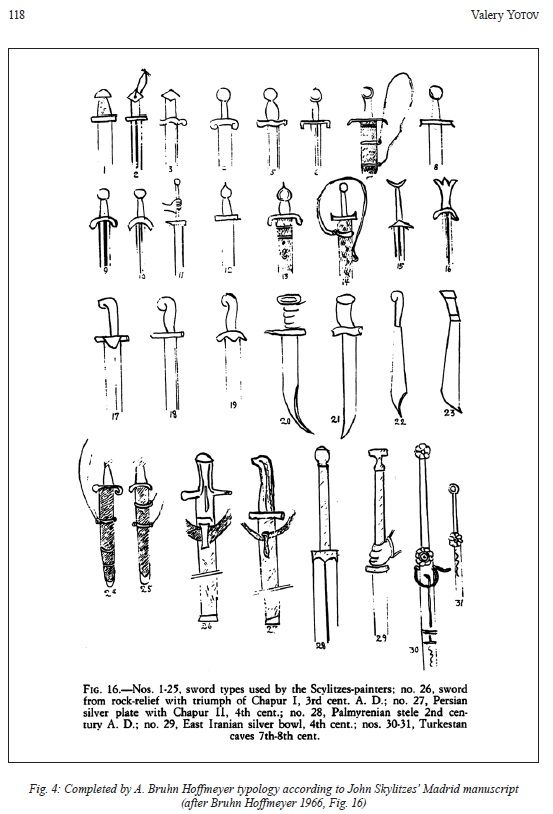

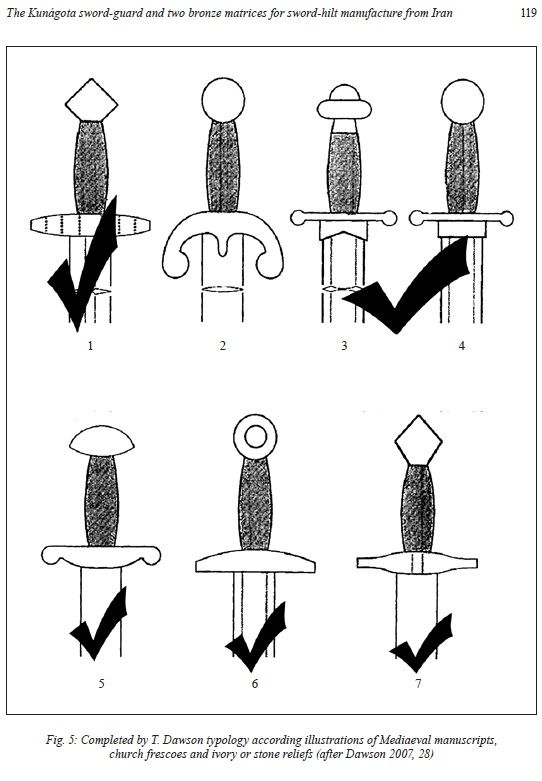

I am familiar with two typological schemes of Byzantine swords which I regard as unreliable or even subjective, mainly because they were based upon images in manuscripts and frescoes and not on real artifacts. Nevertheless I have to note that at this level of research the Kunágota sword-guard and the matrices for sword-hilts from D. Nicolle’s catalogues are similar to Type 4 of Ada Bruhn Hoffmeyer’s scheme based upon John Skylitzes’s Madrid manuscript (Fig. 4) and Type 2 of Timothy Dawson’s scheme, which is based upon images in medieval manuscripts, frescoes as well as stone and bone reliefs (Fig. 5). Among the numerous images collected by D. Nicolle there are several swordguards,which seem similar to the studied artifacts,although the stylization does not enable us to be more specific (NICOLLE 2002a, Figs. 93–94). In his book “Byzantinische Waffen” T. Kolias shared his pessimistic opinion regarding the possibility of creating a more general typology of the various types of weapons and of swords in particular (KOLIAS 1988, 140).3 On the one hand, this pessimism seems justified, but on the other, intensive communication and an exchange of information could provide better options in the future. Having in mind that there is no more detailed information about the provenance of the matrices published in D. Nicolle’s books (Iran in general?), I think that the comparison with the sword-guard from Kunágota will support a more precise date — namely the mid 10th century. A sword found during underwater excavations, and dated to the second half of 10th or the early 11th century (Fig. 3. 1), provides grounds to suggest that sword-guards similar in shape had already been used during the first half of the 11th century (NICOLLE 2002, Cat. Nr. 28).4 In relation with the date again, it is worth remembering T. Kolias’s well-supported opinion

that “when the longer sword (spatha) replaced the shorter sword (gladius), the short sword-guard was introduced in the beginning and after that it gradually

became longer.” According to T. Kolias, until the 10th century sword-guards were short and after the 11th century they gradually became longer.5 All three artifacts have to be related to the military culture of the East Roman Empire-Byzantium as it was also concluded by the Hungarian specialists about the Kunágota sword and by D. Nicolle about the matrices.

Translated by Tatiana STEFANOVA

Valery Yotov

Varna Archaeological Museum

9000 Varna,

41. Bul. Maria Louisa

e-mail: valeri.yotov@gmail.com

BIBLIOGRAPHY

СТАНЧЕВ 1955 С. Станчев: Разкопки и ново-

открити материали в Плиска през 1948 г.

ИАИ 20 (1955) 207.

BAKAY 1967 Bakay, K.: Archäologische Studien

zur Frage der ungarischen Staatsgründung.

ActaArchHung 19 (1967) 105–173.

BÁLINT 1991 Bálint, Cs.: Südungarn im 10.

Jahrhundert. Budapest 1991.

BRUHN HOFFMEYER 1966 A. Bruhn Hoffmeyer:

Military Equipment in the Byzantine

Manuscript of Scylitzes in Biblioteca Nacional

in Madrid. Granada 1966.

DAWSON 2007 T. Dawson: Byzantine Infantryman.

Eastern Roman Empire c. 900–1204.

Oxford 2007.

KISS 1997 Kiss, A.: Frühmittelalterliche byzantinische Schwerter im Karpatenbecken. Acta ArchHung 39 (1997) 193–210.

KOLIAS 1988 T. Kolias: Byzantiniche Waffen. Wien 1988.

KOVÁCS 1993 Kovács, L.: Waffenwechsel vom Sabel zum Schwert. Zur Datierung der Ungarischen Gräber des 10–11. Jahrhunderts mit zweischneidigem Schwert. Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae 6 (1993) 45–60, Abb 1–2.

MÓRA 1926 Móra F.: Lovassírok Kunágotán — Reitergräber aus der Landnahmezeit in Kunágota. Dolg 2 (1926) 123–135.

NICOLLE 1999 D. Nicolle: Arms and Armour of the Crusading Era 1050–1350: Islam, Eastern Europe and Asia. London 1999.

NICOLLE 2002 D. Nicolle: Two Swords from the Foundation of Gibraltar. Gladius 22 (2002) 147–200.

NICOLLE 2002a D. Nicolle (ed.): A Companion to Medieval Arms and Armour. Woodbridge 2002.

1 The Szeged Museum is named after him (http://www.mfm.u-szeged.hu/index_english.php?id=museum-mora).

2 The comparison made by Cs. Bálint with the bronze sword-guard from Pliska published by S. Stanchev is incorrect, see

СТАНЧЕВ 1955, 207, Oбр. 24.

3 T. Kolias notes that it is difficult to develop a typological scheme because of the low number of available artifacts.

4 www.diveturkey.com/inaturkey/serce/arsenal.htm#top

5 „Beim römischen Gladius war kaum eine Parierstange ausgebildet. Als die großen Schwerter den Gladius verdrängt

hatten, setzte sich auch die Parierstange durch; anfänglich nur kurz ausgebildet, nahm sie an Länge allmählich zu… Ab

dem 10.–11. Jahrhundert erfährt die Parierstange eine Verlängerung” (KOLIAS 1988, 143).

Download or view PDF here: Kunagota Sword.pdf (2.49 MB)

By Professor Valery YOTOV

In 1926 a sword with a bronze sword-guard from Kunágota (Békés County, Southeast Hungary) was published by F. Móra (MÓRA 1926, 123–135) the remarkable researcher and director of the Szeged Museum (Fig. 1).1 In several articles published by Hungarian specialists in recent decades, this interesting artifact (its sword-guard being the main issue commented upon) was defined as not being typical for the Carpathian territory and was subsumed under a group of swords regarded as being of Byzantine origin (BAKAY 1967, 172; BÁLINT 1991, 110,Abb. 31; KISS 1997). The sword was discovered in a destroyed grave together with a couple of stirrups, two earrings and a solidus of the Byzantine Emperor Romanos I (920–944) (Fig. 2). Both the grave and the cemetery are dated, beyond any doubt, to the period between 930s and 950s (KOVÁCS 1993, 46, 51). Until now the Kunágota sword, and the swordguard especially, were not compared to artifacts similar in shape (BÁLINT 1991, 110).2 This has also been noted in the analytical work of A. Kiss (KISS 1997, 200). During a visit to the Institute of rchaeology in Budapest, and due to the kind help provided by Hungarian colleagues, I had the opportunity of getting acquainted with articles and books by the English researcher D. Nicolle on medieval arms and armour. In the chapters discussing the Byzantine Empire, together with a large number of artifacts, the presents two bronze matrices for the manufacture of sword-hilts: one of them now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fig. 3. 3) and the other from a private collection (Fig. 3. 2). Both are believed to have come from Iran. D. Nicolle wrote that both artifacts are dated to the 12th–13th to 14th centuries, but he also drew attention to the fact that “the dating of these objects is very difficult” (NICOLLE 1999, Kat. Nr. 543-a, 676; NICOLLE 2002, Kat. Nr. 29-A, 30).

The Kunágota sword-guard has several main typical features — a high sleeve, cylindrical in shape, of the upper section, arch-shaped levers and a sleeve with an ellipsoid bottom section. These characteristics are very close, indeed almost identical to, the shapes that the matrices would produce for the moulds and the manufactured artifacts. It is especially true for the matrix from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which has almost the same curves of the bottom part (the larger sleeve) and the palmette-shaped decoration on the upper part.

I am familiar with two typological schemes of Byzantine swords which I regard as unreliable or even subjective, mainly because they were based upon images in manuscripts and frescoes and not on real artifacts. Nevertheless I have to note that at this level of research the Kunágota sword-guard and the matrices for sword-hilts from D. Nicolle’s catalogues are similar to Type 4 of Ada Bruhn Hoffmeyer’s scheme based upon John Skylitzes’s Madrid manuscript (Fig. 4) and Type 2 of Timothy Dawson’s scheme, which is based upon images in medieval manuscripts, frescoes as well as stone and bone reliefs (Fig. 5). Among the numerous images collected by D. Nicolle there are several swordguards,which seem similar to the studied artifacts,although the stylization does not enable us to be more specific (NICOLLE 2002a, Figs. 93–94). In his book “Byzantinische Waffen” T. Kolias shared his pessimistic opinion regarding the possibility of creating a more general typology of the various types of weapons and of swords in particular (KOLIAS 1988, 140).3 On the one hand, this pessimism seems justified, but on the other, intensive communication and an exchange of information could provide better options in the future. Having in mind that there is no more detailed information about the provenance of the matrices published in D. Nicolle’s books (Iran in general?), I think that the comparison with the sword-guard from Kunágota will support a more precise date — namely the mid 10th century. A sword found during underwater excavations, and dated to the second half of 10th or the early 11th century (Fig. 3. 1), provides grounds to suggest that sword-guards similar in shape had already been used during the first half of the 11th century (NICOLLE 2002, Cat. Nr. 28).4 In relation with the date again, it is worth remembering T. Kolias’s well-supported opinion

that “when the longer sword (spatha) replaced the shorter sword (gladius), the short sword-guard was introduced in the beginning and after that it gradually

became longer.” According to T. Kolias, until the 10th century sword-guards were short and after the 11th century they gradually became longer.5 All three artifacts have to be related to the military culture of the East Roman Empire-Byzantium as it was also concluded by the Hungarian specialists about the Kunágota sword and by D. Nicolle about the matrices.

Translated by Tatiana STEFANOVA

Valery Yotov

Varna Archaeological Museum

9000 Varna,

41. Bul. Maria Louisa

e-mail: valeri.yotov@gmail.com

BIBLIOGRAPHY

СТАНЧЕВ 1955 С. Станчев: Разкопки и ново-

открити материали в Плиска през 1948 г.

ИАИ 20 (1955) 207.

BAKAY 1967 Bakay, K.: Archäologische Studien

zur Frage der ungarischen Staatsgründung.

ActaArchHung 19 (1967) 105–173.

BÁLINT 1991 Bálint, Cs.: Südungarn im 10.

Jahrhundert. Budapest 1991.

BRUHN HOFFMEYER 1966 A. Bruhn Hoffmeyer:

Military Equipment in the Byzantine

Manuscript of Scylitzes in Biblioteca Nacional

in Madrid. Granada 1966.

DAWSON 2007 T. Dawson: Byzantine Infantryman.

Eastern Roman Empire c. 900–1204.

Oxford 2007.

KISS 1997 Kiss, A.: Frühmittelalterliche byzantinische Schwerter im Karpatenbecken. Acta ArchHung 39 (1997) 193–210.

KOLIAS 1988 T. Kolias: Byzantiniche Waffen. Wien 1988.

KOVÁCS 1993 Kovács, L.: Waffenwechsel vom Sabel zum Schwert. Zur Datierung der Ungarischen Gräber des 10–11. Jahrhunderts mit zweischneidigem Schwert. Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae 6 (1993) 45–60, Abb 1–2.

MÓRA 1926 Móra F.: Lovassírok Kunágotán — Reitergräber aus der Landnahmezeit in Kunágota. Dolg 2 (1926) 123–135.

NICOLLE 1999 D. Nicolle: Arms and Armour of the Crusading Era 1050–1350: Islam, Eastern Europe and Asia. London 1999.

NICOLLE 2002 D. Nicolle: Two Swords from the Foundation of Gibraltar. Gladius 22 (2002) 147–200.

NICOLLE 2002a D. Nicolle (ed.): A Companion to Medieval Arms and Armour. Woodbridge 2002.

1 The Szeged Museum is named after him (http://www.mfm.u-szeged.hu/index_english.php?id=museum-mora).

2 The comparison made by Cs. Bálint with the bronze sword-guard from Pliska published by S. Stanchev is incorrect, see

СТАНЧЕВ 1955, 207, Oбр. 24.

3 T. Kolias notes that it is difficult to develop a typological scheme because of the low number of available artifacts.

4 www.diveturkey.com/inaturkey/serce/arsenal.htm#top

5 „Beim römischen Gladius war kaum eine Parierstange ausgebildet. Als die großen Schwerter den Gladius verdrängt

hatten, setzte sich auch die Parierstange durch; anfänglich nur kurz ausgebildet, nahm sie an Länge allmählich zu… Ab

dem 10.–11. Jahrhundert erfährt die Parierstange eine Verlängerung” (KOLIAS 1988, 143).

.png?width=1920&height=1080&fit=bounds)