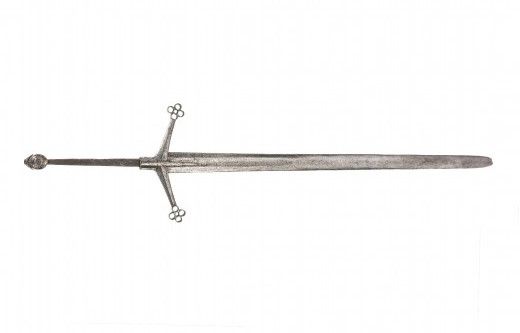

Scottish Claymore w/ Oakeshott Type XIIIa Blade

Jan 27, 2015 3:28:46 GMT

Post by Jack Loomes on Jan 27, 2015 3:28:46 GMT

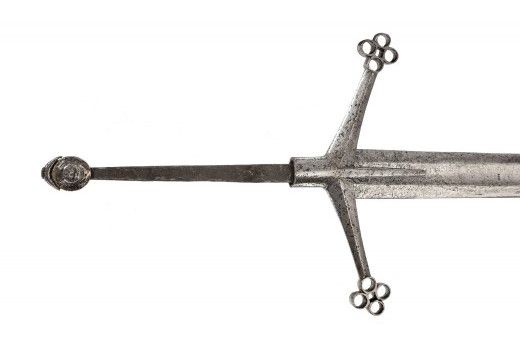

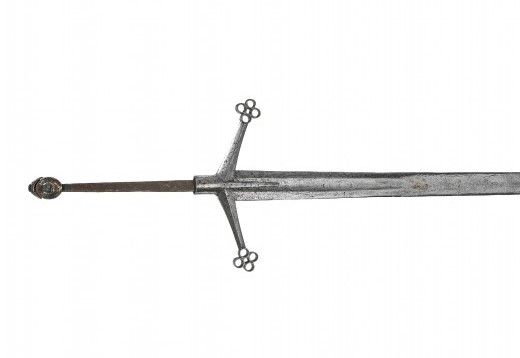

The hilt has downward sloping quillons of diamond section emanating from the base of a high collar, tapering towards their terminals, which are forged from one piece to create their distinctive quatrefoil shapes. Beneath the collar a pair of langets erupt from the base to extend for equal lengths down the blade, either side retaining evidence of fine line decoration extending across the front and sides of each langet. The slightly ovoid pommel is constructed characteristically of two bossed outside plates brazed with latten onto a middle band. The tang protrudes through a crescent-shaped pommel-cap which protected the hollow pommel from damage when the tang was peened over during the assembly of the sword.

The broad, gently tapering blade is formed with a central fuller which extends for twelve inches either side of the hilt; the fuller contains a running wolf inlaid in latten on one side and an orb and cross-in-splendour on the reverse. Inside the fuller an armourer’s mark is stamped in the form a heater-shaped shield, inside which an arrow, above a cross inside a circle, appears in relief. This mark is typical of a number of blade-makers producing similar blades in Solingen in the late 16th century. On each side of the blade the mark is flanked by two numerals, one indistinct, but taken together, the four probably form the date 1574. The sword is in fine condition with pitting commensurate with its age, with a minor old chip to the tip.

Our sword is a particularly fine example of a 16th century Scottish claymore – the two-handed sword of the Scottish Highlands and Isles. ‘Claymore’ is the Anglicised version of the Gaelic term Claidheamh-mor, meaning ‘Great Sword’, and it has often been inappropriately used to refer to Scottish basket-hilted swords carried by Highland regiments. The origin of the true Highland claymore emanates from a much earlier period of Scottish history that is less understood but intriguing. The elegant, well proportioned and sleek profile of a genuine claymore is instantly recognisable. The distinctive cross-guard, with its high collar and langets beneath, has an ancestry which can be traced back to the single-handed swords of the late Viking era in Scotland and the Western Isles. Only forty or so examples of genuine claymores are known to exist today, and most are in public and institutional collections. As a group, the surviving swords are also in varying states of restoration, repair and condition. Our sword is not only a rare survivor but is a fine example of the type. It lacks its grip but it has never been dismantled and retains its classic proportions.

Four outstanding examples, including our sword, are illustrated among others by Laking in A Record of European Armour and Arms. The first is a claymore once owned by Noel Paton, now in the National Museums of Scotland (no. a.1905.634); the second is the ‘Breadalbane’ claymore, from the Rutherford Stuyvesant Collection, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (no. 54.46.10) and the third is the one housed in the British Museum (no. OA.3189 PRN: 7064). Our sword is the fourth in Laking’s notable sequence of outstanding examples, illustrated and described as a ‘claidheamh-mor . . . In a private collection in Perth’.

The earliest representation of a claymore in its fully developed form appears on a grave slab in Kirkapoll churchyard on the island of Tiree and is dated 1495. The latest is the depiction of a man wearing armour and holding a claymore, point down, sculpted into the left side pillar of the Upper Hall fireplace of Huntly Castle, some time around 1600. Between these extremes other dated representations are known, notably at Oransay Priory and at Rodel Church on Harris, in the Hebrides, where MacDuffie chiefs of Colonsay and MacLeods of Dunvegan on Skye are interred. They are all of hand-and-a-half size, slightly smaller and therefore more manoeuvrable than larger Continental two-handers. Interestingly, claymores are generally shown in scabbards but none survive today; most of these depictions lie in the Western Highlands and Isles.

By the end of the 15th century the claymore had reached the peak of its development, suited for the tactics, technology and practicalities attached to warfare in the Highlands, Western Isles and surrounds. This perfection of the sword design created a consistency of form over a long period of time, lasting for more than a century. The clan warriors equipped with these swords generally moved over long distances by foot, over rocky terrain, or by galley across water, travelling light and in an unencumbered self-sufficient manner, sustained by what they could carry and take from the land. The 16th century, the period with which the claymore is associated, was one of the bloodiest in Highland and Scottish history. The period is not well recorded in the Highlands; the Highlanders and Islanders spoke Gaelic and lived in a bardic clan culture with little need or inclination to keep written records. This contrasts quite markedly with our understanding of the later Jacobite Rebellions of the 17th and 18th centuries.

In the 14th and 15th centuries the Lordship of the Isles, a semi-independent regional kingdom, governed the Western Highlands and Isles. This was a period of relative peace, with the Western clans held in check by an alliance which governed from a parliament at Finlaggan on the Isle of Islay. The Lord of the Isles was a vassal of the Scottish crown; due to a mix of internal struggles within the pre-eminent MacDonald families, duplicity and treasonable dealings with the English against the Scottish crown, King James IV forfeited and dissolved the Lordship in 1493 when the estates and titles of John MacDonald II passed to the crown. This did not lead to any increased control over this remote region, as a weak central government and the absence of the regional cohesion once provided by the Lordship unleashed the leading clans and their followers into a century of bitter, long-lasting and bloody feuds where the strongest Western clans, including the MacLeans, MacDonalds, MacLeods and MacNeills, devastated each others’ lands and populations often with genocidal intent. This was their heyday known in Gaelic as linn nan creach – ‘the time of raids’. The chiefs held sway as local warlords over the lands they held, either with or without legal title, accountable only to themselves and influenced only by the most ominous local threats and opportunities. The central and northern Highlands, traditionally, geographically and politically closer to the Scottish crown, behaved in turn in a similar manner, exploiting local opportunities in the absence of strong central authority. However, it was the Western clans that harboured the biggest suspicion and resentment from the Scottish kings. Under the reign of James VI of Scotland (1566–1625) the divergence between the Scottish crown and the Gaelic-speaking clans was growing. While previous kings had feared the uncontrollable nature of these remote clans, they did at least show some respect in acknowledging Gaelic customs and speaking the language. James VI would have none of it and looked to Europe for civilising and aspirational influences to guide his reign. Under his kingship the Gaelic language became known as ‘Erse’ or Irish, now seen as non-Scottish and alien. James tolerated the clans in the eastern and southern Highlands which bordered the ‘civilised’ Lowlands but still looked down upon them as tribal and backward-looking. Those in the west and in the Isles, the area where the claymore is the most significant cultural icon of the 16th century, he regarded contemptuously as ‘void of the knawledge and feir of God’ who were prone to ‘all kynd of barbarous and bestile cruelteis’.

The Western clans in the 16th century were also a significant irritant to the Scottish kings, and in particular to James VI, because of their proximity to, and their relations with, Ireland. Ireland was not fully under English control in the 16th century and Scottish, English and resident Irish clans, nobles and magnates were frequently warring with each other for control of lands and resources. Claims for territory were fought out under pretexts of tenuous loyalties to the aims of either the English or Scottish crowns, who, themselves, would change policy towards Ireland depending upon the status of relations between the two countries at any one time. In the 16th century Ireland was a melting pot of almost permanent hostility, bloodshed and shifting alliances. In this environment the drain on manpower was enormous. The Galloglas kindreds that had supplied Ireland’s hard men for centuries had by now forgotten their native Scottish roots and had developed traditional affiliations with various lords, often fighting on opposing sides and among each other. Against this backdrop a new wave of Scottish mercenaries entered the fray in the 16th century. Known as ‘Redshanks’, these swelling ranks consisted of Scottish Highlanders earning money through one of the few routes open to them, by fighting and by bringing home booty.

While genuine claymores are rare today, Scottish two-handed swords would have been a common enough sight in the 16th century. A letter from Lachlan MacLean of Duart, dated 18 March 1595/6, addressed to the English agent Robert Bowes, specifies what Lachlan claims he could provide for English service in Ireland: 1,500 bowmen and 500 ‘ fyremen’. In this number we will not want our two-handed swords and armour of mail to be used if battle be offered to us; at which time we will change some of our bowmen to use their two-handed swords the time of battle. Examples of this sort of blatant disloyalty to the Scottish crown, pernicious self-interest and haughtiness by the Western chiefs, combined with his helplessness in controlling this behaviour, must have infuriated King James. That the Scots used their two-handed swords in quantity is demonstrated in the record of the defeat of the English forces under the Earl of Chichester at Carrickfergus in Ireland in 1597, which shows that the Scots were carrying ‘sloughe swords’. ‘Slaughter’, ‘slaugh’, ‘slath’ and ‘sloughe’ were contemporary English terms used for the two-handed sword – presumably mainly those carried by Scots mercenaries fighting on both sides because these swords were not a significant feature of the 16th century English armoury. It is also clear that the Highlanders attached a symbolic meaning to the two-handed sword other than its funerary association. An incident in 1595 occurred when a MacDonald leader, while travelling with his men to fight in Ireland, was involved in a dispute in Argyle. As a solution he offered to resolve the matter by fighting a duel with ‘twa handit swordis’. Clearly, a clan leader (and indeed his opponent), by volunteering to fight a duel, presumably with claymores, must have been trained, probably from a very young age, in its use as a ‘one-on-one’ weapon.

The claymore came to the end of its effective working life at the beginning of the 17th century. Queen Elizabeth I of England died childless and in 1603 James VI of Scotland was invited to sit on the throne of England as James I of England and VI of Scotland. Within a few years a relative calm descended on Ireland. The vying factions were no longer able to trade shallow and potentially lucrative allegiances to conflicting national interests now that one king sat on the thrones of England and Scotland. It was apparent to King James that he now had the opportunity to bring these troublesome clans to heel. The Statutes of Iona enacted in 1609 are generally seen today as a reform process begun by King James to extirpate Gaelic culture in the Highlands and the traditional way of life of the clan chiefs. An earlier period of consultation in 1608 had made the King’s position clear with regard to the clans and weapons ‘that they shall forbear wearing any kind of armour (especially guns, bows, and two-handed swords) except only one-handed swords and targes’. Thus the manufacture and use of the claymore gradually declined after 1609, until only a few swords remained with noble families for ceremonial use. The hilts of many would probably have been re-forged into basket hilts and the blades ground down to suit.

Provenance: - Private Collection, Scotland

- W. Keith Neal Collection

- Earlshall Collection

- Private Collection, Germany

Size: Overall length 126.4 cm / 49¾ in Blade length 94.5 cm / 37¼ in

For more information on Oakeshott Type XIIIa Swords see this extract from Ewart Oakeshott's Records of the Medieval Sword: sword-site.com/thread/152/oakeshott-xiiib-records-medieval-sword

Source: www.peterfiner.com/current-stock/item/2088/

.png?width=1920&height=1080&fit=bounds)