Possible Sword of Ivan the Terrible

Nov 24, 2014 7:52:33 GMT

Post by Jack Loomes on Nov 24, 2014 7:52:33 GMT

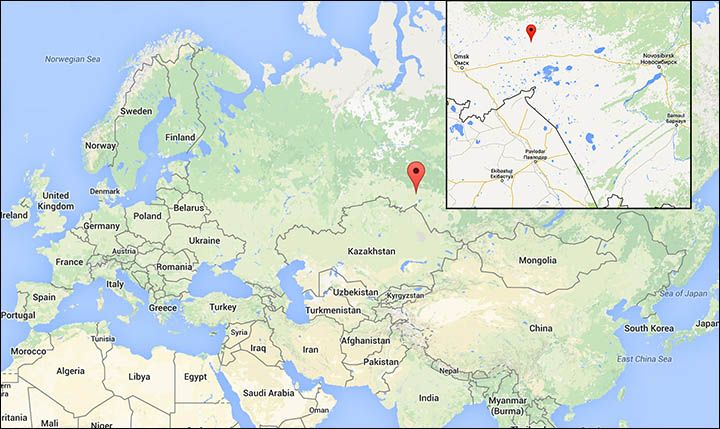

The medieval sword was discovered buried under a tree in Novosibirsk region, and scientists are keen to unlock its secrets. The weapon was unearthed by accident in 1975 and remains the only weapon of its kind ever found in Siberia.

An exciting new theory has now emerged that it could have belonged to Tsar Ivan the Terrible, and came from the royal armoury as a gift at the time of the conquest of Siberia. The hypothesis, twinning an infamous Russian ruler and a revered battle hero, could turn it into one of the most interesting archaeological finds in Siberian history, though for now much remains uncertain.

What Siberian experts are sure about is that the beautifully engraved weapon was originally made in central Europe, and most likely in the Rhine basin of Germany before going to the Swedish mainland, or the island of Gotland, to be adorned with an ornate silver handle and Norse ruse pattern.

The scientists would be keen to hear from European experts who could throw more light on its origins.

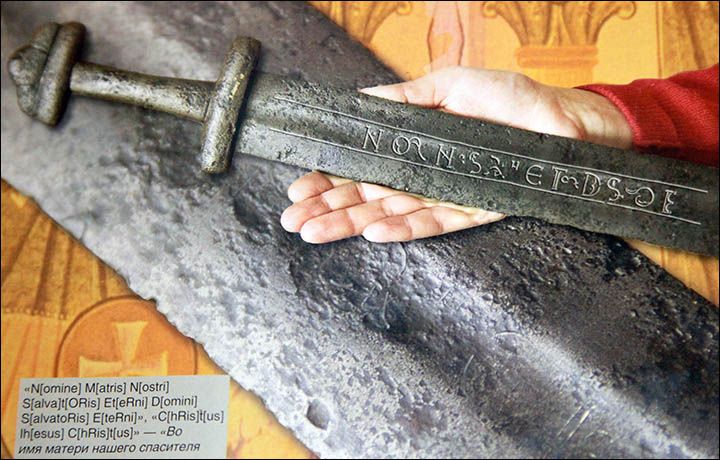

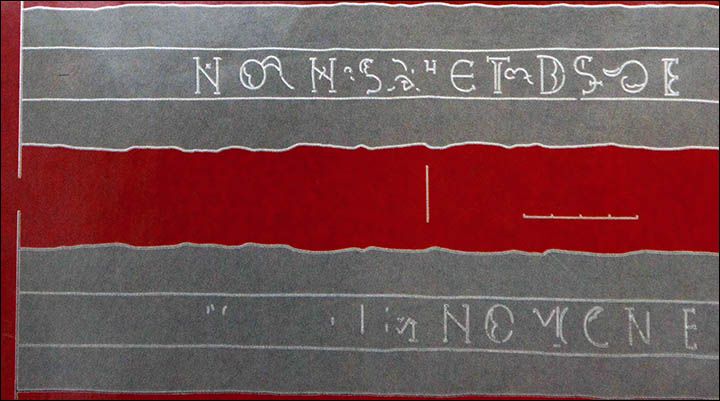

'Both sides of the blade have 'rune' inscription which was abbreviated', said archaeologist Vyacheslav Molodin, the man who led the excavation - in Vengerovo district - which found the weapon. 'The style of calligraphy proves that it was made by people with knowledge of advanced epigraphic writing techniques'.

Russia's leading experts at the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg decoded the Latin wording on the one metre long blade.

The main inscription reads: N[omine] M[atris] N[ostri] S[alva]t[ORis] Et[eRni] D[omini] S[alvatoRis] E[teRni], with an additional one on the same side of the blade saying C[hRis]t[us] Ih[esus] C[hRis]t[us]. This means:'In the name of the mother of our saviour eternal, eternal Lord and Saviour. Christ Jesus Christ.'

The inscription on the reverse side is harder to read, but the first word 'NOMENE' - clearly seen - helps reconstruct the rest as 'N[omine] O[mnipotentis]. M[ateR]. E[teRni] N[omin]e', which means 'In the name of the Almighty. The Mother of God. In the name of Eternal'.

There has been widespread debate about how the sword ended up in Russia, with assumptions it was either carried along a trade route, or taken as a spoil of war from skirmishes in the region. In one of the hypothesis, Academician Molodin has suggested the blade - currently stored in the collections of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography in Novosibirsk - could have been taken from Ivan the Terrible's armoury and brought to Siberia by the legendary warrior Ivan Koltso, ahead of the conquest of the region.

It was during Ivan's reign in the late 16th century that Russia started large scale exploration and colonisation of Siberia. Cossack leader Yermak Timofeyevich was hired to take on the Tatar forces under Khan Kuchum and Murza Karachi and lead the eastward expansion of the empire, with the sword a possible gift from the Kremlin.

The sword was uncovered at the base of a tree in the Baraba forest-steppe, less than three kilometres from where it is thought Koltso, Yermak's closest ally, died in battle. He was declared hero in February 1583, with church bells ringing out in Moscow, when it was announced he and Yermak had taken the capital of the Siberian Khanate, Kashlyk. But his new-found celebrity status did not last long, and he was killed with 40 men during an ambush 18 months later.

Molodin puts a health warning on his new theory but says: 'Imagine the last battle of the Cossack detachment headed by Ivan Koltso. The attack was unexpected. Picture someone immediately being killed by a treacherous stab in the back, and someone else grabbing a sword to fight the advancing Tatars.

'They are unequal forces and the Cossacks are trying to break through the crowds of enemies, but the ranks of the fighters are melting rapidly. Ivan strikes not one opponent. In his hands, the glittering giant sword, a gift from the Russian Tsar.

'In desperation Ivan and a few survivors of the Cossacks literally hack their way to their waiting horses.

'Ivan's leg is already in the stirrup and he is racing on the steppe, with his horse taking him further from the bloody battle. Behind him they chase, with arrows flying. And then, suddenly, the sword falls out of the hands of the hero and drops to the ground under a young birch tree.

'I am not sure that I am right, imagining all this, but the legend is really beautiful.'

He told Science First Hand magazine: 'I must note that none of the scientists mentioned it, perhaps because they didn't take it seriously. The only person who really liked that theory was (noted) Academician (Alexei) Okladnikov. He even mentioned it in one of his last works.

'The hypnotise looks so brave and even fantastical that these days it is unlikely that I would mention it in a scientific work. But on the other hand, it does look very beautiful, plus life can often be more incredible than anything fantastical.

'Even now when I am writing this I believe that we should not exclude the version that the sword could have got to Baraba together with Yermak's squadrons. Despite his Cossacks having sabres and firearms, they were still using swords. So it was quite possible they were using them during that trip'.

It was during the summer of 1975 that Molodin, then a young archaeologist, had been working on the banks of the River Om with a group of students from Omsk and Novosibirsk. Their aim was to study the settlements and cemeteries of the Bronze Age, with a focus on group burials.

At a separate site another group of students had been excavating near a large birch tree, but were under instruction from Molodin not to go near it, certain that no one was buried there. However, Alexander Lipatov, the head of the excavation team, disobeyed the brief and stumbled upon what they thought was a rusty scythe just five centimetres under the grass. As they dug further it became apparent it was a large sword.

Mr Molodin told The Siberian Times: 'The sword wasn't hidden deliberately, or 'buried'. It was lying at a depth of 3-5 cm, right under the soil near the birth tree which was close to an old road. I remember the moment we found it as if it was yesterday.

'We were not supposed to work in the area where we found the sword. It was one of my younger colleagues Alexander Lipatov who decided to 'prolong' the excavation site towards a big birch tree. I remember getting annoyed when I saw it - the area along the birch tree roots was visibly very hard to dig, while my estimates were that the burial mound was not stretching as far as the tree, so there was no point to clear up that space anyway.

'I expressed my reservations about it to Alexander, and he accepted them, but said that he was nervous about making a mistake in defining the site's borders and decided to go a bit further 'just in case'.

'If it wasn't for his 'mistake' we would have never found the sword.

'It was close to lunch time when I was suddenly asked to come to that plot of land near the birch tree to 'check up some piece of iron', as they said. 'Most likely it would be a scythe', I thought to myself as I walked towards the site where they found it.

'Looking back, I see how it was a pure stroke of luck. Every man in our expedition longed to take it and hold it his hands, it was an incredible piece of armament'.

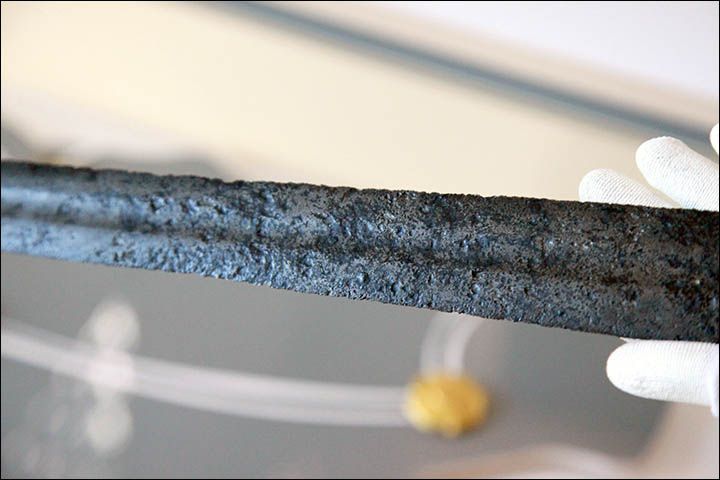

Mr Molodin told Science First Hand magazine: 'Carefully and slowly we cleaned the soil off, uncovering a strip of iron, which was wider at one end, and narrower at the other. It took us an hour to clear the soil completely to see a massive sword, about a metre long with a typical iron hilt of medieval knight's swords with a clearly expressed crossbar guard and tripartite pommel.

'It was incredibly well-preserved, yet I was scared to raise it from the ground. I was scared it would fall into pieces in my hands.

'Finally I put my thin bladed knife underneath the sword and raised it... You know, I've seen swords like this in museums and in scientific books, but it was my first time ever to hold it in my hands. It was as if it just descended from some knights' fairytale.

'I slowly twisted it, noting sparkles of silver on the guard and blade. It was so well preserved that you could in fact use it in the battle almost straight away. Others took to look at the find, too.

'Finally like a water through rushing through a dam, the shock of realising what we've just found broke through and we began talking all at the same time. I can't describe the feeling of surprise and excitement.

'How did it get here, in the heart of the Western Siberia, this clearly so European looking medieval sword? How did it preserve so well? Where did it come from? '

Swords such as these were not typical in Russia or across Asia, and it was more similar to those widely used by European knights. After extensive research on ancient weapons, Vyacheslav Molodin prepared a report on his findings and concluded it was from Europe and dated to the late 12th or early 13th century.

Questions as to how the sword reached Russia from Sweden have been asked since 1976, with the first theory that it was carried during trade missions.

According to Arab historians, in the middle of the 12th century there was an ancient northern path through Russia to the River Ob, called the 'Zyryanskaya road' or 'Russky tes'. Over the centuries archaeologists have found a treasure trove of coins, silver vessels and medieval jewellery in the Urals and lower reaches of the Ob, having travelled from the west.

The downside to this theory is that the steppe, where the sword was found, is separated from the lower and middle Ob by hundreds of kilometres of rugged forests and swamps. Others have argued the weapon could easily have travelled east as a result of bartering, or as a spoil of war from skirmishes between the Turkic people of the steppe and the nomadic Urgic population of the Siberian taiga.

Source: siberiantimes.com/science/casestudy/features/f0013-could-rare-sword-have-belonged-to-ivan-the-terrible/

.png?width=1920&height=1080&fit=bounds)