A New Byzantine Type of Swords - Professor Valeri Yotov

Jun 26, 2013 10:55:05 GMT

Post by Jack Loomes on Jun 26, 2013 10:55:05 GMT

By Professor Valeri Yotov

A NEW BYZANTINE TYPE OF SWORDS

(7th – 11th CENTURIES)

In his book Byzantinische Waffen, T. G. Kolias shared his pessimistic opinion about the possibility of creating a more general typology of the various types of Byzantine weapons and swords in particular. He notes that it is difficult to develop a typological scheme, because of the low number of artifacts available1. The Hungarian scholar B. Fehér also held that “the few surviving specimens do not enable typological classifications”2. With a little more hope looked to this problem J. Haldon at his article “Some Aspects of Early Byzantine Arms and Armour”. In a small passage concerning swords and single-edged weapons, he notes that “it may be possible to begin establishing a concrete typology”3.

A little surprising, but according to B. Fehér, as an attempt to Byzantine typology of swords can be set actually the texts in two excellent Arabic written sources of the 9th century: the book of al-Kindi: The swords and their types ... and of the 11th century author al-Biruni: Kitab ... in the chapter „On iron“4.

I am familiar with two modern typological schemes of Byzantine swords suggested by Ada Bruhn Hoffmeyer (based upon the John Skylitzes’s Madrid manuscript)5 and the one of Timothy Dawson based upon images in mediaeval manuscripts, frescoes as well as stone and bone reliefs6. I regard both typologies as unreliable or even subjective mainly, because they were based upon images in art and not on real artifacts. Viewing those two typological schemes T. G. Kolias suggested that: “into information about weaponry in artistic images, you must approach with extreme caution”7.

1 T. G. Kolias, Byzantinische Waffen. Wien 1988, 140.

2 B. Fehér, Byzantine sword art as seen by the Arabs. – Acta Ant. Hung., 41, 2001, 157–164, note 18.

3 J. Haldon, Some Aspects of Early Byzantine Arms and Armour. – In. D. Nicolle (ed.), A Companion to Medieval Arms and Armour, Woodbridge, 2002, 73.

4 See: B. Fehér, Byzantine sword art as seen by the Arabs…

5 A. B. Hoffmeyer, Military Equipment in the Byzantine Manuskript of Scylitzes in Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid, Granada, 1966, Fig. 16.

6 T. Dawson, Byzantine Infantryman. Eastern Roman Empire c. 900–1204. Oxford, 2007, 28.

7 T. G. Kolias, Byzantinische Waffen..., 33.114 Valeri Yotov

In separate articles, a few some European scholars made the identification of swords from a defined geographical area as being of Byzantine origin. Firstly I would mention the article of A. Kiss about the swords from Carpathian Basin8. In two simultaneously published articles (1991) two authors, who deal with swords and sabers by the time of Avar Khaganate also defined a type as Byzantine: É. Garam on its designated type I9 and L. Simon10. L. Simon noted that without a doubt, among the vast amount of weapons collected by him (193 pieces of swords and sabers) a lot were fruit of gifts or spoils of Byzantium.

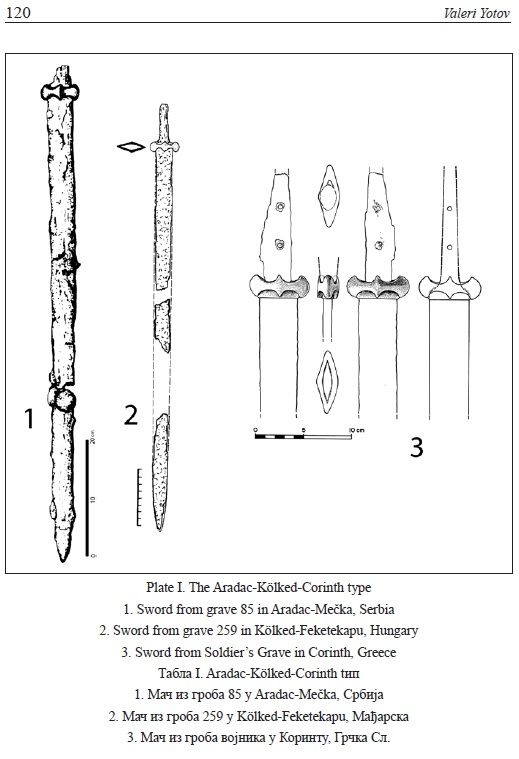

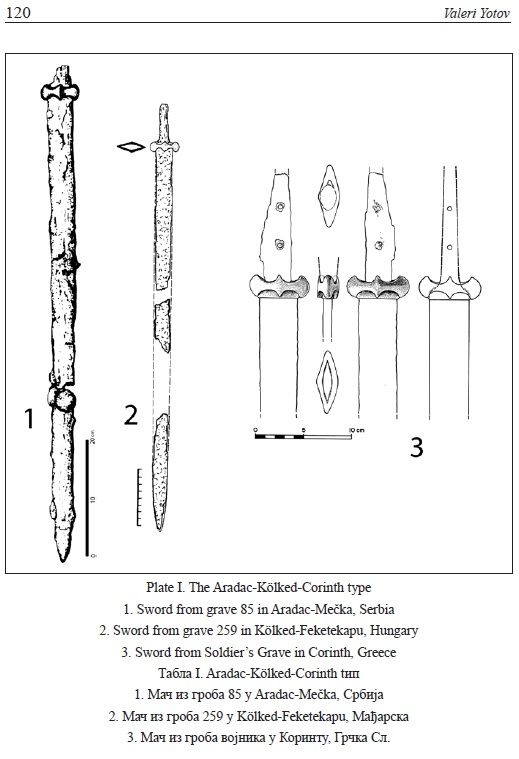

To my knowledge, one of the first attempts to determine the type of Byzantine swords was made by the G. D. Weinberg – publisher of the sword in Soldier’s Grave in Corinth (final of 6th – beginning of 7th centuries)11. Later, A. Kiss gave this type the name “Aradac-Korinth-Pergamon”. He thinks that the swords discovered in these places (type) have a southern origin12. A few years ago at the conference in Budapest, the German scholar C. Eger called the type “Aradac-Kölked-Corinth” (Plate I: 1–3), which is undoubtedly more accurate. The systematization of C. Eger actually adds new material to the sword classification of Weinberg and fuses it with new findings and examples of artworks13.

Recently, on the typology of the Byzantine swords paid attention also the Serbian scholar M. Aleksić. The finds used by Aleksić: a sword and two sword-guards (found in Bulgaria and cited according to my book14) really have common features, but these examples and parallels ultimately did not allow the author to differentiate separate types, but only to refer the problem15.

For the production of weapons in the Byzantine Empire there are only a few written sources that are discussed repeatedly. In Ceremonial book there are refers about the manufacturing of arms in Constantinople16. T. G. Kolias also notes that the empire has adjusted quickly to the best, technical innovations of

8 A. Kiss, Frühmittelalterliche Bizantinische Swherter im Karpatenbecken. – Acta Arch. Hung., XXXIX, 1997, 193–210.

9 É. Garam, Awarenzeitliche Gräber von Tiszakécske-Óbög. Angaben zu den Säbeln und zu den geraden, einschneidigen Schwertern der Awarenzeit. – Comm. Arch. Hung., 1991, 164, Abb. 10.

10 L. Simon, Korai avar kardok (= Early Avar swords). – Studia Comitatensia, 22. Szentendre, 1991, 263–346.

11 G. D. Weinberg, A Wandering Soldier’s Grave in Corinth. – Hesperia, 4, 1974, 512–521.

12 A. Kiss, Frühmittelalterliche Bizantinische Swherter im Karpatenbecken…, 194–198.

13 C. Eger, Die Schwerter mit bronzener Parierstange vom Typ Aradac-Kölked-Korinth. Zur Frage byzantinischer Blankwaffen des ausgehenden 6. und 7. Jahrhunderts. – Acta Arch. Hung., 2011 (forthcoming). I would like to express my deeply thanks to Dr Eger for the information about his article.

14 В. Йотов. Въоръжението и снаряжението от българското средновековие (VІІ–ХІ в.). Варна 2004, 40–46.

15 M. Aleksić, Some Typological Features of Byzantine Spatha. – Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta, XLVII, 2010, 121–136.

16 See: T. G. Kolias, Byzantinische Waffen..., 135. Ni{ i Vizantija IX 115 its opponents (often its neighbors)17. Thus, is difficult to determine if some of the weapons mentioned in separate studies, particularly swords are Byzantine, Arabic, Indian, etc.18. Anyway these swords are found inside the territory formerly belonging to the Empire, and this is a good departure data.

B. Fehér assumed that only metallurgical analysis could resolve the problem with determined the swords from Byzantine time, but such practice is almost impossible to be made by one single researcher. Additionally I must say that the written sources in turn does not always give us clarity and what is the difference between two edged swords or one edged swords (saber)19. Last but not least we should individuated the concept of “Byzantine” swords: not all the swords used inside the Roman army of Byzantium (many mercenaries, like the Varangians, employed their swords in service20) but the swords effectively produced by Roman manufactories.

In this respect I think the most correct issue is to focus on the weapons of the Byzantine Empire in general. By then, a weapon that has been affirmed in the marches and battles, employed both from regular and allied troops.

Notes on methodology.

It is known that the study of the bigger number of archaeological finds is primarily related to their systematization. Every single method for systematization (classification, typology) consists of an analysis of the archaeological environment, function, morphological signs, comparing of as more parts as possible.

Especially for swords, and the other stab-cutting weapons, the most often used attribute typological characteristics are related to the handle: the shape of the pommel and especially the sword-guard. In other words, the typology of swords is often “a typology of the sword-guards”.

All classifications of the swords developed by European scholars are in Roman numerals or letters (I, II, II… or A, B, C…) and Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3…). All definite types give historical and cultural characteristics, as well as dating.

As I already mentioned, systematization and chronological-typological characteristics are the instruments by means of which the information is presented in a more suitable order21.

17 Ibidem, 27.

18 Ada Bruhn Hoffmeyer, notes that many of the martial techniques – a sword (saber) especially come to Europe from Islamic world (A. B. Hoffmeyer, Introduction to the History of the European Sword. – Gladius, I, 1961, 43). See also: D. Nicolle commentary from Shipwreck at Serçe Limani, Turkey in: D. Nicolle, Arms and Armour of the Crusading Era, 1050–1350, II. Islam, Eastern Europe and Asia. London, 1999, 122, commentary from Fig. 292: A-P.

19 B. Fehér, Byzantine sword art as seen by the Arabs…, 161.

20 See V.Yotov, The Vikings on the Balkans, Varna, 2003, 5,20,23-26; s. also R. D’Amato, The Varangian Guard,988-1453. Oxford 2010, 36-37;

21 See introduction in my book: В. Йотов. Въоръжението и снаряжението от българското средновековие (VІІ–ХІ в.), 9–12. 116 Valeri Yotov

What are the possibilities of classification of swords used in the Byzantine Empire?

Given wide variety of forms of restraint and extensive territorial coverage from several continents I suggest that the contributions which have been already done revealed that it is difficult from small number of artifacts to complete one typological scheme.

Up to date basis for classification have been done according to swords, parts of swords found during excavations and others discoveries by chance, but in all well dated monuments.

Using close parallels of artistic nature: frescoes, reliefs, etc., only supports but does not solve the problem. However we should remember that: not all that it is represented in the art has been found in archaeology, but all that has been found is represented in the art.

All defined here types are based mostly on uniformity of the shape of sword-guard. Series of more than one: two, three or more identical or very similar by shape details have been also used. A good example is defined by A. Kiss and C. Eger type “Aradac-Kölked-Korinth”, where it concerns almost the same type of sword-guards, it is even possible to be from same casting model as recognized.

New defined types:

The Garabonc type (Plate II: 4–6)

In 1994 B. M. Szőke published the results of the archaeological research of Garabonc-І necropolis in Zala County, southwest of Lake of Balaton in Hungary. The Garabonc-І necropolis has been dated to the second half of 9th century. Very well preserved sword (Plate II: 4) was found in grave 55. B. M. Szőke define that this sword is Byzantine22.

The Garabonc-I sword doesn’t actually has many published parallels. I was very much surprised, when I became aware of a sword (in a private collection – Plate II: 5), found during the Second World War in a trench in the region of Suhaya Gomolsha village, not far away from Kharkov, Ukraine23. It is still unclear whether this finding has any connection to the published necropolis in the same area from the time of Khazars’ Khaganate where many weapons and military equipment, most of which sabers and stirrups have been found24. However, I think that this sword is a close parallel to the Garabonc-I sword.

22 B. M: Szőke, Karolingerzeitliche Gräberfelder I-II von Garabonc-Ófalu. – In: B. M. Szőke, und K. Éry, R. Müller, L. Vándor: Die Karolingerzeit im Unteren Zalatal. Gräberfelder und Siedlungsreste von Garabonc I-II und Zalaszabar-Dezsősziget. – Antaeus, 21. Budapest, 1992, 92–96, taf. 18; 20 63; B. M. Szőke, Karoling-kori szolgálónépi temetkezések Mosaburg/Zalavár vonzáskörzetében: Garabonc-Ófalu I-II. - In: Zalai Múzeum, 5, 1994, 251-317 (http://www.archeo.mta.hu/hun/munkatars/szokebelamiklos/ZM_05_1994.pdf). The sword has been recently published in the impressive catalogue of RZGM (curator Falko Daim), Byzanz, Pracht und Alltag, 2010, 293.

23 The information and photos belong to colleagues of Kharkov University, especially to the professor Sergej Djachkov.

24 В. К. Михеев, Подонье в составе Хазарского каганата. Харьков, 1985, 90, рис. 7–12.

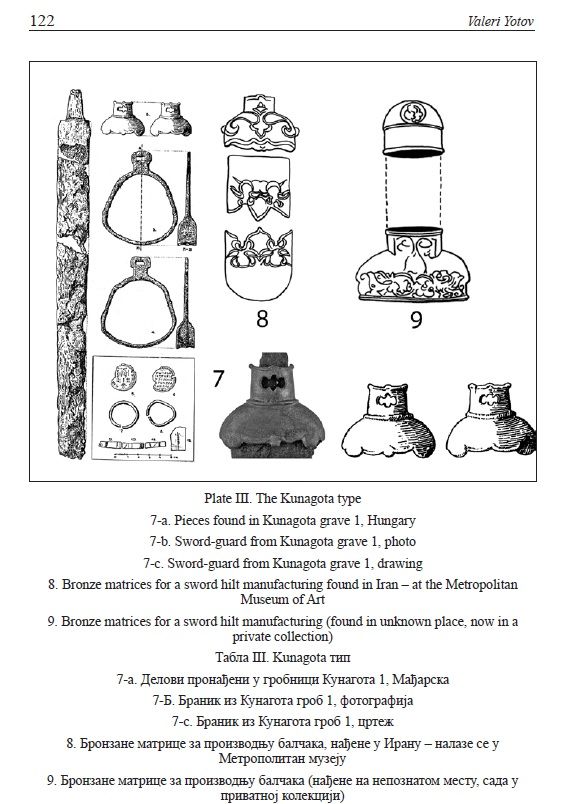

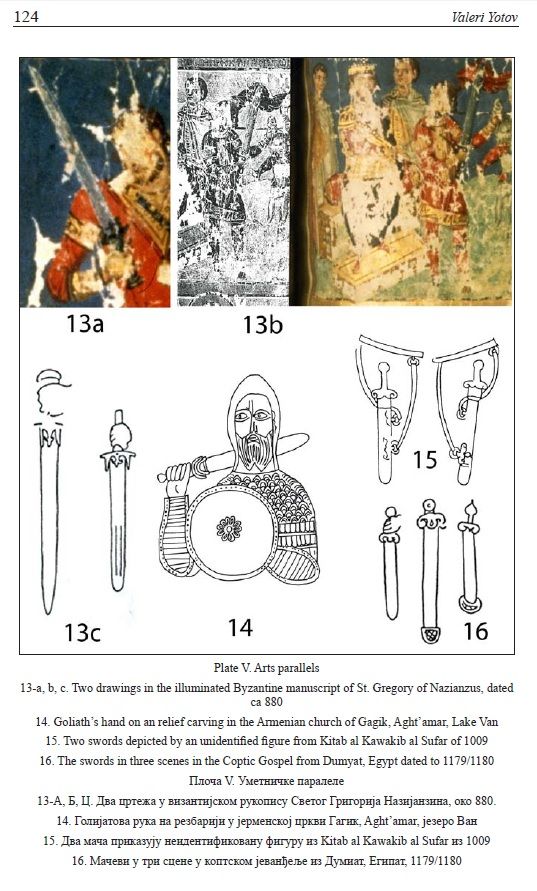

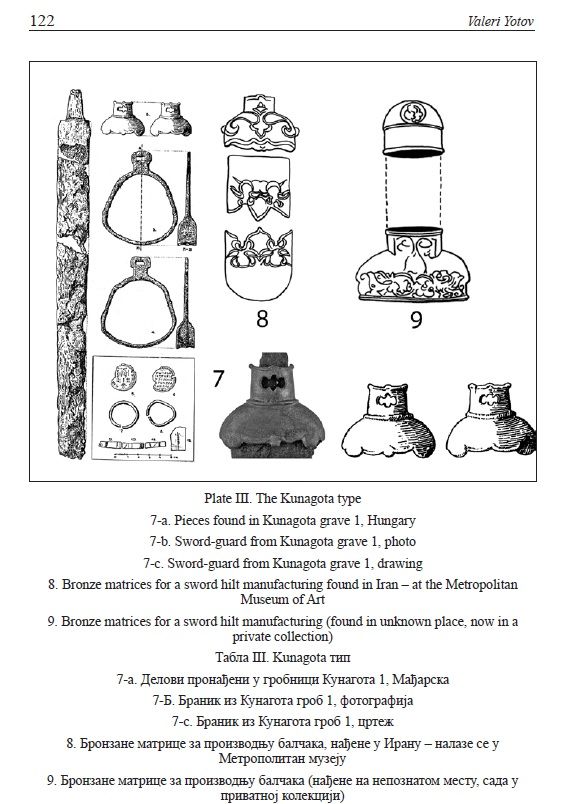

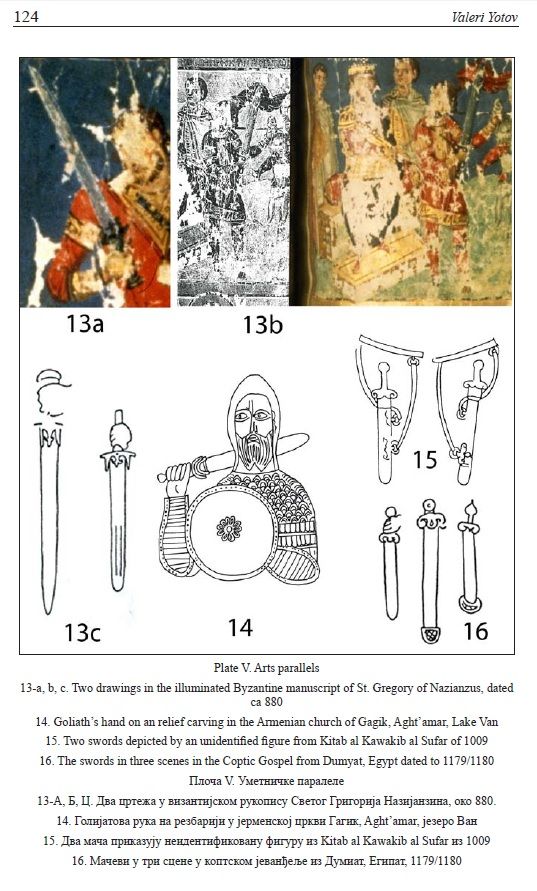

Ni{ i Vizantija IX 117 Another close parallel (Plate II: 6) is a find from a unknown site of the Samanid dynasty period: 8th–9th centuries. The sword has been published recently in a very rich catalogue25. All three swords have analogies among Byzantine representational art monuments from the middle and the second half of the 9th century. I have in mind the swords represented in two miniatures (Plate V: 13) of the illuminated Byzantine manuscript of St. Gregory of Nazianzus, dated ca 880.26 The Kunagota type (Plate III: 7–9) This type is based on a sword and bronze sword-guard (Plate III: 7) from Kunágota, Békés County in Southeast Hungary.27 In several articles published by Hungarian specialists during the recent decades, this interesting artifact (its sword-guard being the main issue commented upon) was defined as not being typical for the Carpathian territory and was subsumed under a group of swords regarded as being of Byzantine origin28.

The sword was discovered in a destroyed grave together with a couple of stirrups, two earrings and two silver coins of the Byzantine Emperors Romanos I Lakapenos –Constantinos VII Porphyrogenetos – Stefanos – Constantinos (931–944). Both the grave and the cemetery have been dated beyond any doubt to the period between 930s and 950s29. Until now, the Kunágota sword and the sword-guard especially were not compared to artifacts similar in shape30. This has also been noted in the analytical work of A. Kiss 31.

In the articles and the books by the English researcher D. Nicolle on Mediaeval arms and armors, together with a large number of artifacts he presents two bronze matrices for a sword-hilt manufacturing. One of them is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Plate III: 8) and the other one in a private collection (Plate III: 9). Both of them are believed to come from Iran. D. Nicolle wrote that both artifacts are dated to the 12th/13th – 14th centuries, but he also drew attention to the fact that “the dating of these objects is very difficult”32.

25 The Arts of the Muslim Knight: The Furusiyya Art Foundation Collection. Milano, 2008 (ed. B. Mohamed), picture in p. 37, info in cat No 8.

26 Manuscript Greek 510. Paris, Bibliothéque Nationale, folio 137 and folio 215v. S. H. Omont, Miniatures des plus anciens manuscrits grecs de

la Bibliotheque Nationale du VI au XIV siecle (Paris 1929), Pls. XXXII (137v), XXXIX (215v);

27 First publication: F. Móra, Lovassírok Kunágotán – Reitergräber aus der Landnahmezeit in Kunágota. – In: Dolgοzatok, 2, 1926, 123–135.

28 K. Bakay, Archäologische Studien zur Frage der ungarishen Staats-gründung. – Acta Arch. Hung., XIX, 1967, 172; Cs. Bálint, Südungarn im 10. Jaгrhundert. Budapest, 1981, 110, Abb. 31; A. Kiss, Frühmittelalterliche Bizantinische Swherter…, 193–210.

29 L. Kovacs, Waffenwechsel vom Sabel zum Schwert . Zur Datierung der Ungarischen Graber des 10–11. Jaгrhunderts mit Zweischeidigem Schwert. – Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae, VI. Lodz 1993, 46, 51.

30 Cs. Bálint, Südungarn im 10. Jaгrhundert…, 110. The comparison made by Cs. Bálint with the bronze sword-guard from Pliska published by S. Stanchev is incorrect, see: S. Stančev. Razkopki i novootkriti materiali v Pliska prez 1948 g. – IAI, ХХ, 1955, 207, fig. 24.

31 A. Kiss, Frühmittelalterliche Bizantinische Schwerter…, 200.

32 D. Nicolle. Two Swords from the Fondation of Gibraltar. – Gladius, XXII, 2002, Kat. 118 Valeri Yotov

The Kunágota sword-guard has several main typical similar features: a high sleeve, cylindrical in shape of the upper section, arch-shaped levers and a sleeve with an ellipsoid shaped bottom section. These characteristics are very close, indeed almost identical to the shapes that the matrices would produce for the moulds and the artifacts manufactured. It is especially true for the matrix from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which has almost the same curves of the bottom part (the larger sleeve) and the palmette-shaped decoration on the upper part.

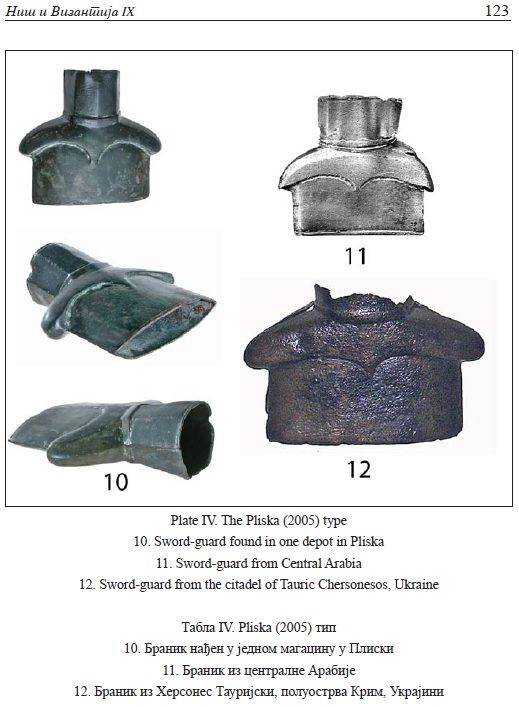

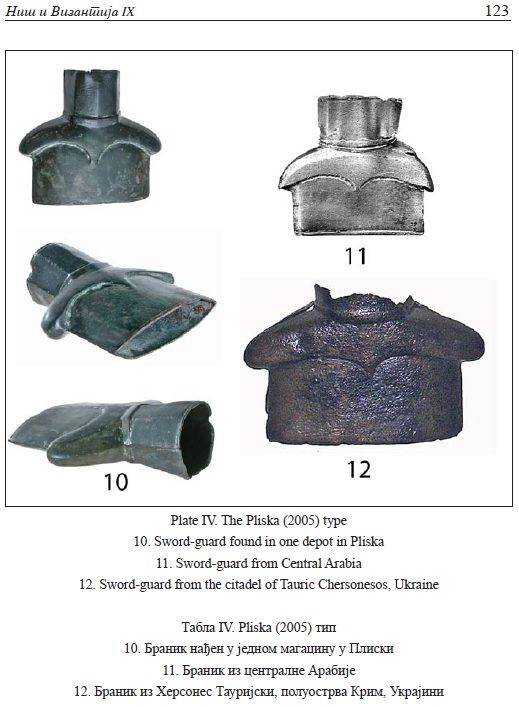

The Pliska (2005) type (Plate IV: 10–12)

Three uniformity sword-guards define this type. All of them have been made of bronze and manufactured by casting and have a height of 67 мм and 64 mm width. Their forms are very close: the upper part of the sleeve represents an octagonal prism, while its bottom part has a double-ellipsoidal shape.

The first (Plate IV: 10) one was discovered during archaeological excavation in 2005 in Pliska, the first capital of the First Bulgarian Kingdom. It was found in a pit having a brick-plated bottom, together with other artifacts made of iron, copper, bronze, bone and glass (twenty five pieces in total). The excavator P. Georgiev has already published an artifact of this finding: a bronze mould for manufacturing of Arabian coins (bractea or a dinar, dirham, or a fels imitation. According to the author, the pit with finds should be dated back to the first half of 11th century and was related to the first raids of Petchenegs south of the Danube River (1030–1040)33.

The second one sword-guard (Plate IV: 11) was found in Central Arabia (Syria?). It has been repeatedly depicted by D. Nicolle. According to him, the sword-guard has been made of iron (“iron quillon of sword from al-Rabadhah way-station on Darb Zubaydah pilgrim road, Islamic 8th–9th century” Dept. of Archaeology, King Sa`ud University, Riyadh”)34. D. Nicolle’s statement about the metal used for manufacturing the sword-guard is in fact a mistake, which was recently corrected in an article published in a popular Russian magazine on weaponry35.

The third one sword-guard (Plate IV: 12) was found in 1905, in the southwestern part of the citadel of Tauric Chersonesos (modern Sevastopol, on the Crimean Peninsula)36.

D. Nicolle presented many pictorial parallels of the Kunagota and Pliska-2005 types with similar sword and sword-guards in manuscripts, wall-paintings, etc. I shall mention only those closer in shape to the discussed ones, although they have been depicted in a quite schematic way. I have in mind the sword shown in Goliath’s hand on an relief carving (Plate V: 14) in the Armenian Nr. 29-A, 30; D. Nicolle, Arms and Armour of the Crusading Era…, Kat. Nr. 543-a, 676.

33 П. Георгиев. Калъп за монетовидни знаци (брактеати) с псевдокуфически надпис от Плиска. – В: Сто години от рождението на д-р Васил Хараланов. Шумен, 2008, 353–364.

34 D. Nicolle, Byzantine and Islamic Arms and Armour; Evedence for Mutual Influence. – Graeco-Arabica, 4, 1991, 312, Fig. 3-a; D. Nicolle. Two Swords…, 164, Kat. Nr. 38.

35 Фарисы. Тяжелая конница сарацин (1050–1250 г.г.). – Новый солдат, 25, 2002, 9–10.

36 В. Йотов. Перекрестье меча из Херсонеса. – Античная древность и средние века, 39. Екатеринбург, 2009, 251–261.

Ni{ i Vizantija IX 119

church of Gagik, Aght’amar, Lake Van, dated to the early 10th century37, as well as two swords depicted by an unidentified figure (Plate V: 15) from Kitab al Kawakib al Sufar of 100938 and the swords in three scenes (Plate V: 16) in the Coptic Gospel from Dumyat, Egypt dated to 1179/118039.

These defined types of swords (identical or very similar sword-guards) are a good basis for create in a future a more detailed developed a typology of swords of the Eastern Roman Empire.

Валери Јотов

НОВИ ВИЗАНТИЈСКИ ТИП МАЧЕВА (VII - XI ВЕК)

Аутор је представио један већ добро познат тип мачева под називом “Aradac-Kölked- Corinth” (by A. Kis and C. Eger), и дефинисао три нова типа мачева и браника византијског времена од VII до XI века.

Нови дефинисани типови:

Гарабон тип - Овај тип заснован је на мачу нађеном у Гарабону-І некрополи, Мађарска, другом пронађеном у близини Харкова, Украјина и мачу који припада Саманидској династији из периода између VIII и IX XXXXXвека, као што је објављеном у једном каталогу. Све три мача су аналогни мачевима репрезентативним споменицима византијске уметности из средине и другој половини IX века - два цртежа у византијском рукопису Светог Григорија, око 880.

The Kunagota тип - Овај тип базира се на мачу и бронзаном бранику за мач из Кунагота, југоистичне Мађарске, и две бронзане матрице за производњу балчака за мач (сада у Метрополитан музеју и у приватној колекцији).

Плиска тип (2005) - Три униформна браника за мач дефинишу овај тип. Сви они су направљњни од бронзе и произведени ливењем, висине од 67цм и ширине 64мм. Њихови облицу су веома слични: горњи део рукава представља осмоугаона призма, док доњи део им облик двоструке елипсе. Први је откривен током археолошких ископавања у 2005., у Плиски, првој престоници Првог бугарског царства. Други је браник пронађен у централној Арабији (Сирија?). Трећи је штитник пронађен 1905., на југозападном делу Херсонес Тауријски (Севастопољ, на Кримском полуострву).

Ови дефинисани типови мачева (идентични или веома слични браници) су добра основа за будућу, детаљније развијену типологију мачева Источног Римског царства.

37 P. Donadebian / J. Thierry, Les Arts Arméniens. Paris, 1987, 379, Fig. 251. D. Nicolle. Byzantine and Islamic Arms and Armour…, Fig. 30.

38 D. Nicolle. Byzantine and Islamic Arms and Armour…, Fig. 46 (Abbasid Iraq or Fatimid Egypt).

39 D. Nicolle. Byzantine and Islamic Arms and Armour…, Fig. 48: a-c.

Source:

academia.edu/1975521/Byzantine_Time_Swords_10th-11th_Centuries_in_Romania

www.ni.rs/byzantium/doc/zbornik9/PDF-IX/08%20Valeri%20Yotov.pdf

A NEW BYZANTINE TYPE OF SWORDS

(7th – 11th CENTURIES)

In his book Byzantinische Waffen, T. G. Kolias shared his pessimistic opinion about the possibility of creating a more general typology of the various types of Byzantine weapons and swords in particular. He notes that it is difficult to develop a typological scheme, because of the low number of artifacts available1. The Hungarian scholar B. Fehér also held that “the few surviving specimens do not enable typological classifications”2. With a little more hope looked to this problem J. Haldon at his article “Some Aspects of Early Byzantine Arms and Armour”. In a small passage concerning swords and single-edged weapons, he notes that “it may be possible to begin establishing a concrete typology”3.

A little surprising, but according to B. Fehér, as an attempt to Byzantine typology of swords can be set actually the texts in two excellent Arabic written sources of the 9th century: the book of al-Kindi: The swords and their types ... and of the 11th century author al-Biruni: Kitab ... in the chapter „On iron“4.

I am familiar with two modern typological schemes of Byzantine swords suggested by Ada Bruhn Hoffmeyer (based upon the John Skylitzes’s Madrid manuscript)5 and the one of Timothy Dawson based upon images in mediaeval manuscripts, frescoes as well as stone and bone reliefs6. I regard both typologies as unreliable or even subjective mainly, because they were based upon images in art and not on real artifacts. Viewing those two typological schemes T. G. Kolias suggested that: “into information about weaponry in artistic images, you must approach with extreme caution”7.

1 T. G. Kolias, Byzantinische Waffen. Wien 1988, 140.

2 B. Fehér, Byzantine sword art as seen by the Arabs. – Acta Ant. Hung., 41, 2001, 157–164, note 18.

3 J. Haldon, Some Aspects of Early Byzantine Arms and Armour. – In. D. Nicolle (ed.), A Companion to Medieval Arms and Armour, Woodbridge, 2002, 73.

4 See: B. Fehér, Byzantine sword art as seen by the Arabs…

5 A. B. Hoffmeyer, Military Equipment in the Byzantine Manuskript of Scylitzes in Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid, Granada, 1966, Fig. 16.

6 T. Dawson, Byzantine Infantryman. Eastern Roman Empire c. 900–1204. Oxford, 2007, 28.

7 T. G. Kolias, Byzantinische Waffen..., 33.114 Valeri Yotov

In separate articles, a few some European scholars made the identification of swords from a defined geographical area as being of Byzantine origin. Firstly I would mention the article of A. Kiss about the swords from Carpathian Basin8. In two simultaneously published articles (1991) two authors, who deal with swords and sabers by the time of Avar Khaganate also defined a type as Byzantine: É. Garam on its designated type I9 and L. Simon10. L. Simon noted that without a doubt, among the vast amount of weapons collected by him (193 pieces of swords and sabers) a lot were fruit of gifts or spoils of Byzantium.

To my knowledge, one of the first attempts to determine the type of Byzantine swords was made by the G. D. Weinberg – publisher of the sword in Soldier’s Grave in Corinth (final of 6th – beginning of 7th centuries)11. Later, A. Kiss gave this type the name “Aradac-Korinth-Pergamon”. He thinks that the swords discovered in these places (type) have a southern origin12. A few years ago at the conference in Budapest, the German scholar C. Eger called the type “Aradac-Kölked-Corinth” (Plate I: 1–3), which is undoubtedly more accurate. The systematization of C. Eger actually adds new material to the sword classification of Weinberg and fuses it with new findings and examples of artworks13.

Recently, on the typology of the Byzantine swords paid attention also the Serbian scholar M. Aleksić. The finds used by Aleksić: a sword and two sword-guards (found in Bulgaria and cited according to my book14) really have common features, but these examples and parallels ultimately did not allow the author to differentiate separate types, but only to refer the problem15.

For the production of weapons in the Byzantine Empire there are only a few written sources that are discussed repeatedly. In Ceremonial book there are refers about the manufacturing of arms in Constantinople16. T. G. Kolias also notes that the empire has adjusted quickly to the best, technical innovations of

8 A. Kiss, Frühmittelalterliche Bizantinische Swherter im Karpatenbecken. – Acta Arch. Hung., XXXIX, 1997, 193–210.

9 É. Garam, Awarenzeitliche Gräber von Tiszakécske-Óbög. Angaben zu den Säbeln und zu den geraden, einschneidigen Schwertern der Awarenzeit. – Comm. Arch. Hung., 1991, 164, Abb. 10.

10 L. Simon, Korai avar kardok (= Early Avar swords). – Studia Comitatensia, 22. Szentendre, 1991, 263–346.

11 G. D. Weinberg, A Wandering Soldier’s Grave in Corinth. – Hesperia, 4, 1974, 512–521.

12 A. Kiss, Frühmittelalterliche Bizantinische Swherter im Karpatenbecken…, 194–198.

13 C. Eger, Die Schwerter mit bronzener Parierstange vom Typ Aradac-Kölked-Korinth. Zur Frage byzantinischer Blankwaffen des ausgehenden 6. und 7. Jahrhunderts. – Acta Arch. Hung., 2011 (forthcoming). I would like to express my deeply thanks to Dr Eger for the information about his article.

14 В. Йотов. Въоръжението и снаряжението от българското средновековие (VІІ–ХІ в.). Варна 2004, 40–46.

15 M. Aleksić, Some Typological Features of Byzantine Spatha. – Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta, XLVII, 2010, 121–136.

16 See: T. G. Kolias, Byzantinische Waffen..., 135. Ni{ i Vizantija IX 115 its opponents (often its neighbors)17. Thus, is difficult to determine if some of the weapons mentioned in separate studies, particularly swords are Byzantine, Arabic, Indian, etc.18. Anyway these swords are found inside the territory formerly belonging to the Empire, and this is a good departure data.

B. Fehér assumed that only metallurgical analysis could resolve the problem with determined the swords from Byzantine time, but such practice is almost impossible to be made by one single researcher. Additionally I must say that the written sources in turn does not always give us clarity and what is the difference between two edged swords or one edged swords (saber)19. Last but not least we should individuated the concept of “Byzantine” swords: not all the swords used inside the Roman army of Byzantium (many mercenaries, like the Varangians, employed their swords in service20) but the swords effectively produced by Roman manufactories.

In this respect I think the most correct issue is to focus on the weapons of the Byzantine Empire in general. By then, a weapon that has been affirmed in the marches and battles, employed both from regular and allied troops.

Notes on methodology.

It is known that the study of the bigger number of archaeological finds is primarily related to their systematization. Every single method for systematization (classification, typology) consists of an analysis of the archaeological environment, function, morphological signs, comparing of as more parts as possible.

Especially for swords, and the other stab-cutting weapons, the most often used attribute typological characteristics are related to the handle: the shape of the pommel and especially the sword-guard. In other words, the typology of swords is often “a typology of the sword-guards”.

All classifications of the swords developed by European scholars are in Roman numerals or letters (I, II, II… or A, B, C…) and Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3…). All definite types give historical and cultural characteristics, as well as dating.

As I already mentioned, systematization and chronological-typological characteristics are the instruments by means of which the information is presented in a more suitable order21.

17 Ibidem, 27.

18 Ada Bruhn Hoffmeyer, notes that many of the martial techniques – a sword (saber) especially come to Europe from Islamic world (A. B. Hoffmeyer, Introduction to the History of the European Sword. – Gladius, I, 1961, 43). See also: D. Nicolle commentary from Shipwreck at Serçe Limani, Turkey in: D. Nicolle, Arms and Armour of the Crusading Era, 1050–1350, II. Islam, Eastern Europe and Asia. London, 1999, 122, commentary from Fig. 292: A-P.

19 B. Fehér, Byzantine sword art as seen by the Arabs…, 161.

20 See V.Yotov, The Vikings on the Balkans, Varna, 2003, 5,20,23-26; s. also R. D’Amato, The Varangian Guard,988-1453. Oxford 2010, 36-37;

21 See introduction in my book: В. Йотов. Въоръжението и снаряжението от българското средновековие (VІІ–ХІ в.), 9–12. 116 Valeri Yotov

What are the possibilities of classification of swords used in the Byzantine Empire?

Given wide variety of forms of restraint and extensive territorial coverage from several continents I suggest that the contributions which have been already done revealed that it is difficult from small number of artifacts to complete one typological scheme.

Up to date basis for classification have been done according to swords, parts of swords found during excavations and others discoveries by chance, but in all well dated monuments.

Using close parallels of artistic nature: frescoes, reliefs, etc., only supports but does not solve the problem. However we should remember that: not all that it is represented in the art has been found in archaeology, but all that has been found is represented in the art.

All defined here types are based mostly on uniformity of the shape of sword-guard. Series of more than one: two, three or more identical or very similar by shape details have been also used. A good example is defined by A. Kiss and C. Eger type “Aradac-Kölked-Korinth”, where it concerns almost the same type of sword-guards, it is even possible to be from same casting model as recognized.

New defined types:

The Garabonc type (Plate II: 4–6)

In 1994 B. M. Szőke published the results of the archaeological research of Garabonc-І necropolis in Zala County, southwest of Lake of Balaton in Hungary. The Garabonc-І necropolis has been dated to the second half of 9th century. Very well preserved sword (Plate II: 4) was found in grave 55. B. M. Szőke define that this sword is Byzantine22.

The Garabonc-I sword doesn’t actually has many published parallels. I was very much surprised, when I became aware of a sword (in a private collection – Plate II: 5), found during the Second World War in a trench in the region of Suhaya Gomolsha village, not far away from Kharkov, Ukraine23. It is still unclear whether this finding has any connection to the published necropolis in the same area from the time of Khazars’ Khaganate where many weapons and military equipment, most of which sabers and stirrups have been found24. However, I think that this sword is a close parallel to the Garabonc-I sword.

22 B. M: Szőke, Karolingerzeitliche Gräberfelder I-II von Garabonc-Ófalu. – In: B. M. Szőke, und K. Éry, R. Müller, L. Vándor: Die Karolingerzeit im Unteren Zalatal. Gräberfelder und Siedlungsreste von Garabonc I-II und Zalaszabar-Dezsősziget. – Antaeus, 21. Budapest, 1992, 92–96, taf. 18; 20 63; B. M. Szőke, Karoling-kori szolgálónépi temetkezések Mosaburg/Zalavár vonzáskörzetében: Garabonc-Ófalu I-II. - In: Zalai Múzeum, 5, 1994, 251-317 (http://www.archeo.mta.hu/hun/munkatars/szokebelamiklos/ZM_05_1994.pdf). The sword has been recently published in the impressive catalogue of RZGM (curator Falko Daim), Byzanz, Pracht und Alltag, 2010, 293.

23 The information and photos belong to colleagues of Kharkov University, especially to the professor Sergej Djachkov.

24 В. К. Михеев, Подонье в составе Хазарского каганата. Харьков, 1985, 90, рис. 7–12.

Ni{ i Vizantija IX 117 Another close parallel (Plate II: 6) is a find from a unknown site of the Samanid dynasty period: 8th–9th centuries. The sword has been published recently in a very rich catalogue25. All three swords have analogies among Byzantine representational art monuments from the middle and the second half of the 9th century. I have in mind the swords represented in two miniatures (Plate V: 13) of the illuminated Byzantine manuscript of St. Gregory of Nazianzus, dated ca 880.26 The Kunagota type (Plate III: 7–9) This type is based on a sword and bronze sword-guard (Plate III: 7) from Kunágota, Békés County in Southeast Hungary.27 In several articles published by Hungarian specialists during the recent decades, this interesting artifact (its sword-guard being the main issue commented upon) was defined as not being typical for the Carpathian territory and was subsumed under a group of swords regarded as being of Byzantine origin28.

The sword was discovered in a destroyed grave together with a couple of stirrups, two earrings and two silver coins of the Byzantine Emperors Romanos I Lakapenos –Constantinos VII Porphyrogenetos – Stefanos – Constantinos (931–944). Both the grave and the cemetery have been dated beyond any doubt to the period between 930s and 950s29. Until now, the Kunágota sword and the sword-guard especially were not compared to artifacts similar in shape30. This has also been noted in the analytical work of A. Kiss 31.

In the articles and the books by the English researcher D. Nicolle on Mediaeval arms and armors, together with a large number of artifacts he presents two bronze matrices for a sword-hilt manufacturing. One of them is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Plate III: 8) and the other one in a private collection (Plate III: 9). Both of them are believed to come from Iran. D. Nicolle wrote that both artifacts are dated to the 12th/13th – 14th centuries, but he also drew attention to the fact that “the dating of these objects is very difficult”32.

25 The Arts of the Muslim Knight: The Furusiyya Art Foundation Collection. Milano, 2008 (ed. B. Mohamed), picture in p. 37, info in cat No 8.

26 Manuscript Greek 510. Paris, Bibliothéque Nationale, folio 137 and folio 215v. S. H. Omont, Miniatures des plus anciens manuscrits grecs de

la Bibliotheque Nationale du VI au XIV siecle (Paris 1929), Pls. XXXII (137v), XXXIX (215v);

27 First publication: F. Móra, Lovassírok Kunágotán – Reitergräber aus der Landnahmezeit in Kunágota. – In: Dolgοzatok, 2, 1926, 123–135.

28 K. Bakay, Archäologische Studien zur Frage der ungarishen Staats-gründung. – Acta Arch. Hung., XIX, 1967, 172; Cs. Bálint, Südungarn im 10. Jaгrhundert. Budapest, 1981, 110, Abb. 31; A. Kiss, Frühmittelalterliche Bizantinische Swherter…, 193–210.

29 L. Kovacs, Waffenwechsel vom Sabel zum Schwert . Zur Datierung der Ungarischen Graber des 10–11. Jaгrhunderts mit Zweischeidigem Schwert. – Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae, VI. Lodz 1993, 46, 51.

30 Cs. Bálint, Südungarn im 10. Jaгrhundert…, 110. The comparison made by Cs. Bálint with the bronze sword-guard from Pliska published by S. Stanchev is incorrect, see: S. Stančev. Razkopki i novootkriti materiali v Pliska prez 1948 g. – IAI, ХХ, 1955, 207, fig. 24.

31 A. Kiss, Frühmittelalterliche Bizantinische Schwerter…, 200.

32 D. Nicolle. Two Swords from the Fondation of Gibraltar. – Gladius, XXII, 2002, Kat. 118 Valeri Yotov

The Kunágota sword-guard has several main typical similar features: a high sleeve, cylindrical in shape of the upper section, arch-shaped levers and a sleeve with an ellipsoid shaped bottom section. These characteristics are very close, indeed almost identical to the shapes that the matrices would produce for the moulds and the artifacts manufactured. It is especially true for the matrix from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which has almost the same curves of the bottom part (the larger sleeve) and the palmette-shaped decoration on the upper part.

The Pliska (2005) type (Plate IV: 10–12)

Three uniformity sword-guards define this type. All of them have been made of bronze and manufactured by casting and have a height of 67 мм and 64 mm width. Their forms are very close: the upper part of the sleeve represents an octagonal prism, while its bottom part has a double-ellipsoidal shape.

The first (Plate IV: 10) one was discovered during archaeological excavation in 2005 in Pliska, the first capital of the First Bulgarian Kingdom. It was found in a pit having a brick-plated bottom, together with other artifacts made of iron, copper, bronze, bone and glass (twenty five pieces in total). The excavator P. Georgiev has already published an artifact of this finding: a bronze mould for manufacturing of Arabian coins (bractea or a dinar, dirham, or a fels imitation. According to the author, the pit with finds should be dated back to the first half of 11th century and was related to the first raids of Petchenegs south of the Danube River (1030–1040)33.

The second one sword-guard (Plate IV: 11) was found in Central Arabia (Syria?). It has been repeatedly depicted by D. Nicolle. According to him, the sword-guard has been made of iron (“iron quillon of sword from al-Rabadhah way-station on Darb Zubaydah pilgrim road, Islamic 8th–9th century” Dept. of Archaeology, King Sa`ud University, Riyadh”)34. D. Nicolle’s statement about the metal used for manufacturing the sword-guard is in fact a mistake, which was recently corrected in an article published in a popular Russian magazine on weaponry35.

The third one sword-guard (Plate IV: 12) was found in 1905, in the southwestern part of the citadel of Tauric Chersonesos (modern Sevastopol, on the Crimean Peninsula)36.

D. Nicolle presented many pictorial parallels of the Kunagota and Pliska-2005 types with similar sword and sword-guards in manuscripts, wall-paintings, etc. I shall mention only those closer in shape to the discussed ones, although they have been depicted in a quite schematic way. I have in mind the sword shown in Goliath’s hand on an relief carving (Plate V: 14) in the Armenian Nr. 29-A, 30; D. Nicolle, Arms and Armour of the Crusading Era…, Kat. Nr. 543-a, 676.

33 П. Георгиев. Калъп за монетовидни знаци (брактеати) с псевдокуфически надпис от Плиска. – В: Сто години от рождението на д-р Васил Хараланов. Шумен, 2008, 353–364.

34 D. Nicolle, Byzantine and Islamic Arms and Armour; Evedence for Mutual Influence. – Graeco-Arabica, 4, 1991, 312, Fig. 3-a; D. Nicolle. Two Swords…, 164, Kat. Nr. 38.

35 Фарисы. Тяжелая конница сарацин (1050–1250 г.г.). – Новый солдат, 25, 2002, 9–10.

36 В. Йотов. Перекрестье меча из Херсонеса. – Античная древность и средние века, 39. Екатеринбург, 2009, 251–261.

Ni{ i Vizantija IX 119

church of Gagik, Aght’amar, Lake Van, dated to the early 10th century37, as well as two swords depicted by an unidentified figure (Plate V: 15) from Kitab al Kawakib al Sufar of 100938 and the swords in three scenes (Plate V: 16) in the Coptic Gospel from Dumyat, Egypt dated to 1179/118039.

These defined types of swords (identical or very similar sword-guards) are a good basis for create in a future a more detailed developed a typology of swords of the Eastern Roman Empire.

Валери Јотов

НОВИ ВИЗАНТИЈСКИ ТИП МАЧЕВА (VII - XI ВЕК)

Аутор је представио један већ добро познат тип мачева под називом “Aradac-Kölked- Corinth” (by A. Kis and C. Eger), и дефинисао три нова типа мачева и браника византијског времена од VII до XI века.

Нови дефинисани типови:

Гарабон тип - Овај тип заснован је на мачу нађеном у Гарабону-І некрополи, Мађарска, другом пронађеном у близини Харкова, Украјина и мачу који припада Саманидској династији из периода између VIII и IX XXXXXвека, као што је објављеном у једном каталогу. Све три мача су аналогни мачевима репрезентативним споменицима византијске уметности из средине и другој половини IX века - два цртежа у византијском рукопису Светог Григорија, око 880.

The Kunagota тип - Овај тип базира се на мачу и бронзаном бранику за мач из Кунагота, југоистичне Мађарске, и две бронзане матрице за производњу балчака за мач (сада у Метрополитан музеју и у приватној колекцији).

Плиска тип (2005) - Три униформна браника за мач дефинишу овај тип. Сви они су направљњни од бронзе и произведени ливењем, висине од 67цм и ширине 64мм. Њихови облицу су веома слични: горњи део рукава представља осмоугаона призма, док доњи део им облик двоструке елипсе. Први је откривен током археолошких ископавања у 2005., у Плиски, првој престоници Првог бугарског царства. Други је браник пронађен у централној Арабији (Сирија?). Трећи је штитник пронађен 1905., на југозападном делу Херсонес Тауријски (Севастопољ, на Кримском полуострву).

Ови дефинисани типови мачева (идентични или веома слични браници) су добра основа за будућу, детаљније развијену типологију мачева Источног Римског царства.

37 P. Donadebian / J. Thierry, Les Arts Arméniens. Paris, 1987, 379, Fig. 251. D. Nicolle. Byzantine and Islamic Arms and Armour…, Fig. 30.

38 D. Nicolle. Byzantine and Islamic Arms and Armour…, Fig. 46 (Abbasid Iraq or Fatimid Egypt).

39 D. Nicolle. Byzantine and Islamic Arms and Armour…, Fig. 48: a-c.

Source:

academia.edu/1975521/Byzantine_Time_Swords_10th-11th_Centuries_in_Romania

www.ni.rs/byzantium/doc/zbornik9/PDF-IX/08%20Valeri%20Yotov.pdf

.png?width=1920&height=1080&fit=bounds)